Where did the horses we call Garranos come from? What secrets do they hide when they challenge us from the top of the mountains?

- In Prehistory, during the Paleolithic, life on earth was profoundly altered by cooling that caused the occurrence of glaciations and with them, the migration of several species. So, like reindeer, some horses headed north. Others headed south in search of a more benign climate.

In the Iberian Peninsula, a group of horses settled in the North and from this nucleus the Garrano descended, with the status of a native horse since the Middle Paleolithic.

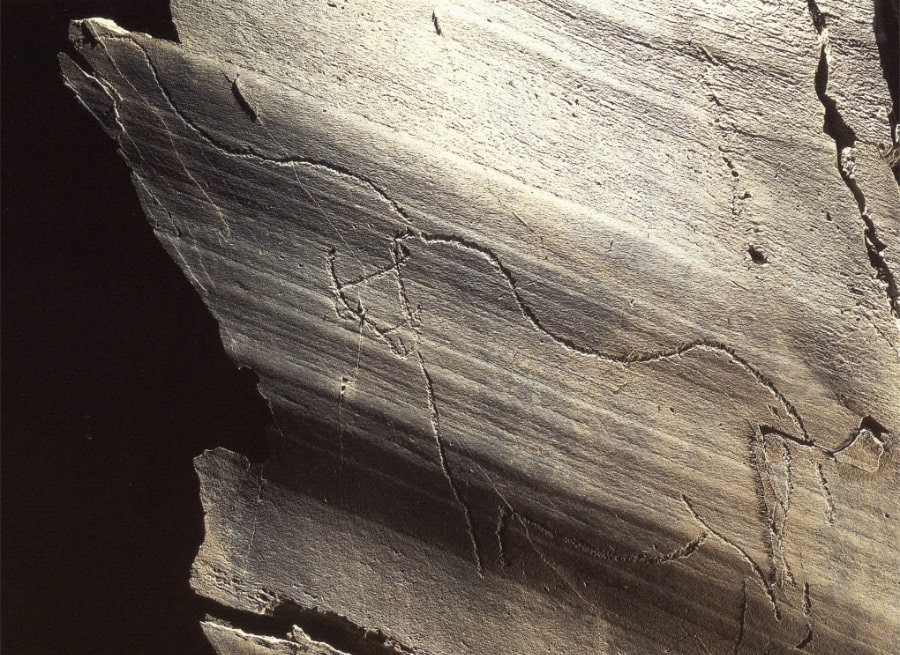

Well-adapted to its new habitat, the Garrano did not leave again. - The nomadic hunter gave way to the sedentary producer and the horse, domesticated, went from target to Man’s best ally. The cave art of the Upper Paleolithic (Foz Côa, Mazouco) is an eloquent testimony to the presence of horses that are not very corpulent and have short extremities, thick coats and a straight or concave head profile, in a faithful portrait of the Garranos of our days.

- In the Iron Age (1st millennium BC), the small and resistant horses introduced by the Celts would have influenced the native populations, evolving into horses of small stature, with a straight or concave head profile, characteristic of cold and humid mountainous regions. The Celtic influence in the origin of the Garrano is reinforced by the name of the small horse being internationalized with the name “pony”, while in Portugal the same etymological root that gave rise to “gearron” (Gaelic) and “garron” (Gaelic) remained.

- The first written references to the small Celtic horses of the Peninsula date back to the Romans. They described them as Asturcones (the current Asturcon, from Asturias), Gallaeci (the current Pura Raça Galega) and Tieldões (our Garrano). They considered them good mountain horses and used them as draft and transport horses, on trips and in courier services, well adapted to mountain paths.

- In the Middle Ages, several references to Garranos appear in Portuguese laws and their trade remained active between the Peninsula, Ireland and England.

They have an important role in the repopulation and settlement of the population in Portuguese territory, constituting, since then, a distinctive element of our national identity. - As part of groups of horses that colonizers took to America, the Garrano also participated in the colonization of the New World. Small but robust, it proved to be the ideal type for traction and agricultural work. In Mexico, the Garrano would have originated the current Galiceño horse, which displays traces of the rusticity and comfortable gaits of its predecessors. In Brazil, the Marchador is one of the breeds originating from the Garranos.

- Rusticity, frugality and longevity, associated with energy, vivacity and resistance, made the Garrano the ideal mount for muleteers in Minho, during the Middle Ages and until the middle of the 20th century. The Búrios, inhabitants of Terras de Bouro, brought the Garrano to this mountainous region, as the most suitable form of personal transport and also for cargo of dry goods and liquids. Ruy d’Andrade (1930) says: “They are tough, can withstand long journeys and can handle a lot of weight. Small 1.20m horses carry riders and loads weighing more than 100kg, without signs of fatigue, along long mountain paths, making frequent journeys of 50 or more kilometres”.

- Couriers and farriers prospered thanks to the Garrano, with a regular presence at fairs such as the Feira dos Vinte in Prado, Feira da Ladra in Vieira do Minho, Feira dos Santos in Pico de Regalados and Feiras Novas in Ponte de Lima.

- Saddlers set up stalls to display and sell harnesses and trappings for riding cattle. Farriers treated horses’ hooves in covered spaces or traveling workshops under trees. The village’s artisans manufactured harnesses, booms, saddles, girths and ropes for carrying loads on their backs, using traditional techniques.

- The Garrano helped with farming, transporting firewood, grass, manure, grains, flour, eggs and chickens, in addition to taking urgent errands and participating in village festivities. Essential in the domestic economy, the Garrano was a true multifunctional helper.

- In the first half of the 20th century, the creators of Garranos continued to be “poor people, who live in mountainous regions, without roads and who need to transport themselves” (Ruy d’ Andrade, 1938). The mechanization of agriculture, the emergence of automobiles and motorbikes would contribute to the lack of interest in these animals as auxiliaries in traditional farming.

- Voted to abandonment, the Garrano returns to the mountain where he appeals to his most remote roots. Threatened, survives. With the collaboration of breeders and technicians, the State recognizes a unique value in this free-range animal population and, in 1993, the Zootechnical Registry/Genealogical Book of the Garrana Breed was created, with the aim of its quantitative and qualitative preservation.

- Exempted from agricultural work, the Garranos joined mountain groups, recreating the patterns of behavior and social organization of their wild ancestors and living at the whim of natural selection. Therefore, with the exception of some animals stabled to support traditional farming, most breeders keep the Garranos in the mountains where they are raised free-range, bringing the animals together once a year for separation of the foals and subsequent sale.